Eruv and Sectarianism in Ancient Judaism: Biblical Background

Talmudic tradition assumes that the permissibility of constructing an eruv is derived from Exodus 16:29;

Each person shall sit in his (or her) place. Let no one go out from his (or her) place on the Sabbath day.

This interpretation seeks to understand the verb yetze as if it were equivalent to the causative yotzi’, “to take out.” The reality, however, is that this verse serves only to locate the origins of this law in the Torah, rather than in the Prophets, an effort consistently undertaken by the rabbis who, unlike the Dead Sea sectarians, wanted to derive all law from the Pentateuch, probably as a polemic against what they saw as the overemphasis on the Prophets by the early Christians. This is true despite the terminological influence that this passage had on M. Shabbat 1:1. Explicit reference to the prohibition on carrying on the Sabbath is found in Jeremiah 17:21-22:

Thus says the Lord: “Take heed to yourselves, and bear no burden on the day of the Sabbath, nor bring it into the gates of Jerusalem. And do not bring out a burden from your houses on the day of… Continue reading

Eruv and Sectarianism in Ancient Judaism: Introduction

The purpose of the presentation that follows is to argue that the Qumran sectarians, usually identified as the Essenes described by Josephus and other Greek-writing authors, prohibited carrying from domain to domain on the Sabbath, basing themselves on certain biblical passages, and that these ancient Jewish sectarians did not have an institution such as the eruv to mitigate the difficulties caused by this prohibition. Further, we will argue that the combination of this prohibition with the absence of an institution to ease the difficulties that it presents characterizes the exegetical trend of the priestly, Zadokite-Sadducee form of Jewish law, as opposed to that of the Pharisaic-rabbinic trend that developed the laws of the eruv. In making this argument, we do not intend to deny the wider ramifications of the institution of the eruv in terms of the nature of the Jewish community and its patterns of residence. Rather, our main argument is intended to show that the eruv is a Pharisaic-rabbinic device in its origins and function. While much of the research to be discussed here was already put forward in my 1975 volume, The Halakhah at Qumran, more recently published texts have confirmed… Continue reading

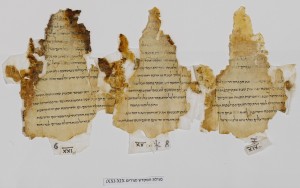

Discovery Times Square Interview

When the Discovery Times Square Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit was running, I was asked some personal and scholarly questions about the Dead Sea Scrolls for the museum’s blog:

When did you first become interested in the Dead Sea Scrolls?

I began working on the Dead Sea Scrolls when I wrote my senior honors paper at Brandeis University in 1970. Then, when I was looking for a topic for my doctoral dissertation that would combine my fields of interest in Bible and rabbinic literature, I realized that the Dead Sea Scrolls were a perfect area of research for me. Of course, at that time only about one-quarter of the material was available, but there was still a lot of work to do.

Over your decades of study, what’s the most surprising thing you’ve learned about the Dead Sea Scrolls?

For me the most surprising thing was to realize that there was an entire library of texts that somehow didn’t enter the mainstream of Jewish literature and thought throughout the ages but that had been part of Jewish culture in Second Temple times, and which did in fact have important influences on Judaism and Christianity. It was amazing… Continue reading