History of Liturgy and Poetry

From first Temple times it is apparent that prayer was a significant part of the individual piety of a fair number of Israelites. Individual prayer was accompanied apparently by poems written for the collective people of Israel. Such prayers seem definitely do have attained a place in the psalmody of the Temple by the second Temple period. In various second Temple texts there are individual and collective prayers, and toward the end of the second Temple period, prayer was becoming institutionalized increasingly, at least as appears from the tannaitic evidence.

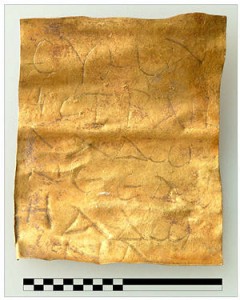

From the set liturgical texts preserved at Qumran, it seems that daily statutory ritual had become part of the life of the sectarians who had separated from the sanctuary that they regarded as impure and improperly conducted. These texts appear not to be of sectarian content and may typify wider trends in the Jewish community. Further, the scrolls give evidence of the twice daily recital of the Shema and the use of mezuzot and phylacteries, some of which were prepared very much in the same way as the Pharisaic-rabbinic tradition requires.

Previous to the Dead Sea Scrolls, the evidence for Hebrew poetry in the postbiblical period was ignored. Hence, the significance of the poems in 1 Maccabees, for example, and even in the New Testament, not to mention early Jewish liturgy preserved in rabbinic texts, or able to be reconstructed from the later prayer texts, was ignored. It was assumed that biblical psalmody was a dead-end tradition to be continued only later by a de novo form of Hebrew liturgical poetry that developed virtually ex nihilo. When the first scrolls were discussed, the Hodayot were taken to be a bad version of Psalms poetry, following the original anti-Jewish trope of the decline of Hebrew literature after the “Old Testament.” No one seemed to realize that we were dealing with the next stage in the history of Hebrew poetry.

Indeed, elements of what are now known as Qumran religious poetry point in various directions toward the style–not content–of the later piyyut. This is clear now especially as regards the reuse of biblical material to form post-Hebrew Bible poems and the tendency to create grammatical forms not previously known. But piyyut, as a corpus related closely to rabbinic literature, takes the rabbinic liturgical character and its content as a starting point and is suffused with rabbinic midrashim and legal rulings, even if some of them are at variance with those taken as normative in the rabbinic legal texts.

How can we explain the contradictory observations that we are making in this presentation? On the one hand, we have emphasized the lack of a literary pipeline from second Temple times into rabbinic texts, beyond that of the Hebrew Scriptures themselves. On the other hand, we have pointed to rich parallels and apparent intellectual interaction between those who left us second Temple texts and those who were apparently the spiritual ancestors of the tannaim, namely the Pharisees. It would seem that here it is the existence of a “common Judaism” that provides the answer.

Wonderful! It seems to me that the paucity of written prayers is due to the destruction of the Temple and subsequent dispersion of the people of God. It would seem that due to the immanent possibility of Roman reconquest of Judea (“signs of the times”) there would be a frenzied rush to write down these liturgical prayers, as at Qumran. There may be a slight possibility that more texts came into the possession of the Crusaders.

The concept of poetic prayer is both aesthetically pleasing and promotes efficient memorization. I wish that more would surface.

Thank you, Prof. Schiffman for your excellent research and for sharing it with the world.