References to Apocryphal Works in Rabbinic Literature

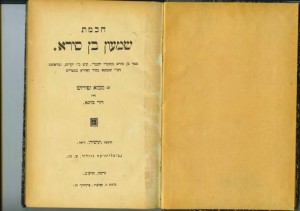

More should be said about explicit references to apocryphal works in rabbinic literature. In fact, rabbinic texts only mention two such works, one being Ben Sira, that the rabbis apparently knew and which is quoted. Another is a certain book called Sefer ben La`ana, the contents of which we have absolutely no idea. The rabbis explicitly prohibit the reading of such books. There is something of an exegetical controversy regarding the meaning of this prohibition. On the one hand, it might be a blanket prohibition forbidding the reading of these texts under any circumstances. The assumption would be that it is forbidden to write any books other than those of Scripture, and therefore to read them. The other interpretation holds that what was prohibited was the public reading of these books as part of the lectionary. In this case, it would be permitted to read such books privately. Such an approach would explain the use of Ben Sira by the rabbis.

More should be said about explicit references to apocryphal works in rabbinic literature. In fact, rabbinic texts only mention two such works, one being Ben Sira, that the rabbis apparently knew and which is quoted. Another is a certain book called Sefer ben La`ana, the contents of which we have absolutely no idea. The rabbis explicitly prohibit the reading of such books. There is something of an exegetical controversy regarding the meaning of this prohibition. On the one hand, it might be a blanket prohibition forbidding the reading of these texts under any circumstances. The assumption would be that it is forbidden to write any books other than those of Scripture, and therefore to read them. The other interpretation holds that what was prohibited was the public reading of these books as part of the lectionary. In this case, it would be permitted to read such books privately. Such an approach would explain the use of Ben Sira by the rabbis.

An interesting parallel that will serve as an example of this phenomenon is the fundamental agreement of the theme of Jubilees, namely that the patriarchs observed all of the laws later to be given at Sinai, with some rabbinic statements and a variety of aggadot. Apparently, this also was part of the common heritage of second Temple Judaism and was taken up by some rabbis.

Numerous sectarian groups are in fact mentioned in rabbinic literature. These groups, however, while apparently practicing modes of piety similar to those that we might expect based on what we now know from the Dead Sea Scrolls, seem in no way to be identifiable with the specific literary works that we have from the second Temple period. Rather, it appears that the later rabbis were aware of the general nature of Judaism in the pre-70 CE period. Indeed, they blamed the phenomenon of sectarianism for the disunity that led to the destruction. However, none of the reports that they preserve can be directly associated with the textual materials from second Temple times. We can only assume, again, that they did not or would not read these materials.

It is necessary to stress that the sect of the Essenes is not mentioned by name in rabbinic literature. Attempts to claim that the Boethusians, baytosim, are in fact none other than the Essenes, have failed to garner significant support because of the philological difficulties involved. While it is possible that some practices of the Essene sect might be described somewhere in rabbinic literature, we see as more fruitful an understanding that the Essenes, as described by Philo and Josephus, most likely shared the Sadducean type halakhic tradition that is indeed polemicized against in rabbinic texts.

One area in which rabbinic literature provides fruitful parallels to sectarian organization is that of the system of entry into the sect and the close link between purity law and sectarian membership. This is because a similar system was in effect for the havurah, a term designating a small group of those who practiced strict purity laws, extending Temple regulations into private life even for non-priests. Scholarly literature has tended to associate this group with the Pharisees, most probably correctly, but the textual evidence seems to separate these terms. In any case, the detailed regulations pertaining to entering the havurah are more closely parallel to the initiation rites of the Qumran sect than they are to the descriptions of the Essenes in Josephus with which they also share fundamental principles.

Some practices of the Qumran sect are indeed mentioned in rabbinic polemics against heterodoxy, termed derekh aheret. But these practices are too few to indicate any kind of real knowledge of the Qumran sect or its practices or of other sectarian groups as a whole.

One interesting areas is that of calendar disputes. For us, it is a commonplace that alongside the calendar of lunar months and solar years used by the pharisaic-rabbinic tradition, others, including the Dead Sea sectarians and the authors of Enoch and Jubilees, called for use of a calendar of solar months and solar years. While we are aware of the fact that numerous problems still beset attainment of a full understanding of the calendrical situation of second Temple Judaism, some part of it was clearly known to the rabbis. Rabbinic sources report that certain sectarians, Sadducees and Boethusians, practiced such a calendar, insisting that the holiday of Shavuot fall on a Sunday and, hence, that the start of the counting of the omer commence on a Saturday night. If indeed these rabbinic references are to the calendar controversy of which we are aware from the scrolls and pseudepigraphal literature, then it seems that the rabbis’ knowledge was quite fragmentary or that they chose to pass on only a small part of the picture. From rabbinic sources one would never have gathered that this sectarian calendar was based on solar months and that it represented an entirely alternative system. All we would have known is that they disagreed on the date of Shavuot.

The bottom line of this is that second Temple literature was not transmitted to the rabbis in any direct way, with the possible exception of Ben Sira, and no Pharisaic teachings in a literary form survive for us from the Pharisees before 70 except in traditions embedded in the rabbinic texts.

From what we have said so far, one would assume that there simply is no relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the rabbinic corpus. After all, virtually nothing of second Temple literature and certainly nothing of the Dead Sea Scrolls sectarian texts appear to have been known to the rabbis. But here is a great irony: when we examine the Judaism of the Dead Sea Scrolls sect as well as that of much of the literature that they preserved we find both similarity and interaction with views preserved in rabbinic texts. Further, fundamental ideas preserved in the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha find their way into the rabbinic tradition. And still to be appropriately explained, rabbinic literature preserves a variety of reflections of historical data preserved for us by Josephus, either in his words or those of his sources, that are somehow reflected in the rather occasional historiographic comments of the sages. In what follows, we will concentrate on examples illustrated by materials preserved in the Qumran corpus, including some that stem from books otherwise preserved in the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha.

From what we have said so far, one would assume that there simply is no relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the rabbinic corpus. After all, virtually nothing of second Temple literature and certainly nothing of the Dead Sea Scrolls sectarian texts appear to have been known to the rabbis. But here is a great irony: when we examine the Judaism of the Dead Sea Scrolls sect as well as that of much of the literature that they preserved we find both similarity and interaction with views preserved in rabbinic texts. Further, fundamental ideas preserved in the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha find their way into the rabbinic tradition. And still to be appropriately explained, rabbinic literature preserves a variety of reflections of historical data preserved for us by Josephus, either in his words or those of his sources, that are somehow reflected in the rather occasional historiographic comments of the sages. In what follows, we will concentrate on examples illustrated by materials preserved in the Qumran corpus, including some that stem from books otherwise preserved in the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha.

>> Another is a certain book called Sefer ben La`ana, the contents of which we have absolutely no idea.<<

I have a theory about this (which may or may not have been propagated by scholars already). There, is in fact, no such book. A book named 'ben La'ana' never existed. SO what is the Talmud referring to? Well your guess is as good as mine but I have a sneaking suspicion that this is a Rabbinic euphemism; an allusion to a popular book authored by the minim (a term referring to any number of schismatics that flourished during the period of the Talmud's redaction). The term 'laana' appears in several other places in Tanakh:

In Deut. 29:17: " shoresh poreh rosh vela'anah" translated as "root bearing poisonous and bitter fruit" or more accurately as "a root that beareth gall and wormwood". That phrase is mentioned in the context of one of the harshest polemics in the Pentateuch, directed against those who deviate from the way of the Lord to worship foreign entities.

In Lamentations 3:15: " הִשְׂבִּיעַנִי בַמְּרוֹרִים, הִרְוַנִי לַעֲנָה"

In Jeremiah 9:14 לכן, כה-אמר יהוה צבאות אלוהי ישראל, הנני מאכילם את-העם הזה, לענה

Ibid 23:15 לָכֵן כֹּה-אָמַר יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת, עַל-הַנְּבִאִים, הִנְנִי מַאֲכִיל אוֹתָם לַעֲנָה, וְהִשְׁקִתִים מֵי-רֹאשׁ

The term mean 'curse' in Arabic.

Shmuel Klein postulates that he was called 'ben laana' because of his sharp and witty sayings (ostensibly contained in this mysterious book). Scroll down to מורי החכמה בישראל

see http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/history/shmot-2.htm

Also you forgot an additional sefer hitzon, mentioned in the Yerushalmi, :Ben Talga (literally 'son of snow').