Canonical History and the Questions of Bible and Biblical

The Perspective of Ancient Judaism

(From a paper presented in Landau, Germany)

This brief statement intends to attack the Bible and its canon in totally Jewish terms. We hope in this way to facilitate a realization of the extent to which the academic discussion of these issues has been conditioned by fundamentally Christian terms, definitions and issues, or by objective academic language that, while welcome, does not represent Judaism in its own light. Let’s save time and call this: “Reclaiming the Jewish Bible”—the title of a book I should probably write.

This brief statement intends to attack the Bible and its canon in totally Jewish terms. We hope in this way to facilitate a realization of the extent to which the academic discussion of these issues has been conditioned by fundamentally Christian terms, definitions and issues, or by objective academic language that, while welcome, does not represent Judaism in its own light. Let’s save time and call this: “Reclaiming the Jewish Bible”—the title of a book I should probably write.

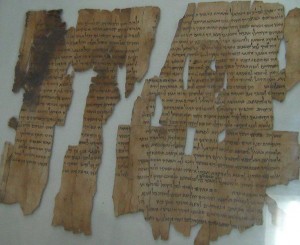

It’s not that Bible isn’t a Jewish term; it is. Ha-sefarim in Dan. 9:2 is translated as en tois biblois, and this is the origin of the term Bible, ta biblia. Judaism, in all its manifestations, has accepted the notion of a set of books that were authoritative. These are books that were believed to emerge from the experience of divine revelation: direct for the Torah; less direct for the Prophets, and indirect for the Writings. To be authoritative, a book must be believed to be divinely inspired in some way. Because they were not seen as authoritative, over twenty books mentioned in the Bible did not survive. Besides divine inspiration there was chronology. No book that did not claim to have been composed before the end of the Persian period could be accepted as inspired, since prophecy was believed to have ended then. So the corpora we call Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha and Dead Sea Scrolls were disallowed.

Yes, the Qumran sect and even the rabbis believed in the continuation of prophecy of some minor type, the “holy spirit” or bat kol (divine echo), but this was simply not the real thing and, hence, none of these later books was (I will use the modern adjective) biblical. Why do I avoid canonical? Because it assumes a meeting (synod)–on the New Testament model–that never happened. The rabbis do argue about whether certain books “defile the hands,” a description that seems to cohere with authoritative status. But we are never told directly that this is the same issue. Nor is there any convincing explanation, except for the phenomenological, for this halakhic category. In any case, the “canonical” debate in Judaism was resolved not by any authoritative body, but rather in a different way—by a consensus of the Jewish people.

Perhaps you have gathered that I reject the open canon theory for the scrolls? Correct. I argue that there was a closed canon, that is, a collection of specific books thought to be authoritative for the group at a specific time. But I also recognize that for some Jewish groups, at certain times, this collection probably contained a few books not in our canon. Why am I so sure? No Dead Sea nor other Second Temple text, nor New Testament nor Rabbinic text, uses any texts as authoritative except the same list we are used to, with a few exceptions that may have been part of someone’s “closed” canon. In the Qumran scrolls, the Hebrew or Aramaic term sefer designated authoritative books and, therefore, is never used–with one exception, sefer serekh–to refer to any books but our Hebrew Bible and the few other books that may have been considered authoritative. Of course we know that the Hellenistic canon included more books. But for Judaism, if it’s authoritative, we expect to see it in action, becoming a building block in the ever-growing Lego City we call the Jewish tradition. If we can’t find traces of its effects, it is because it is not authoritative.

Where did we get the idea of an open canon at Qumran? It is a theory, like the well-known three text theory, that seeks to elevate the Septuagint, with its additional books, as the basis of the New Testament. But, ironically, none of the deuteronocanonical books has been used in the New Testament, although Jude quotes Enoch. To open the canon beyond the deuterocanonical allows the acceptance of the New Testament as ‘”biblical.” Put simply, it is a reflection of Christian theology.

The group of books that were authoritative were the same in all the sects, give or take a few items: Esther, Ben Sira, Enoch, Jubilees and the Levi Document. Contrary to the confused report of one Church Father, who mixed them up with the Samaritans, the Sadducees had the same Bible as the Pharisees and later rabbinic tradition, although the Samaritans did not. In fact, as Josephus proudly proclaimed, to have this Bible was to be a Jew. It was and remains a unifier of the Jewish people.

For Palestinian Jews, this Bible was divided in three parts. I accept the indications of a tripartite (three-part) canon at Qumran, not as a finished product but rather with two stable portions, Torah and Prophets, but with the third still-developing and with some debate still going on. I see evidence for this in the Scrolls, New Testament and Josephus, not to mention the later rabbinic texts.

But to speak of the Jewish Bible is to speak about much more. The notion of some kind of biblical text divorced from its ritual and national-cultural place in Judaism, hence a Bible divorced from exegesis that is not literal or academic, what we call in academic terms the “Hebrew Bible,” is not Jewish. No Jew in the synagogue has ever heard of the “Hebrew Bible.” It is a termed coined by Society of Biblical Literature to solve a problem, and it is indeed a good solution. Pre-modern Jews, even in the Hellenistic period, never heard of JEPD, even though they had their own understanding of the manner in which the word of God was made up of a variety of what we call “documents.” It’s just that to them, all these sections were revealed by God to Moses.

So here is the big irony: Because Jews and Judaism believed that the Bible had been given to them by God through Moses, they were free to allow its traditions to expand through exegesis. Because they believed in a fixed text and canon, they could allow the Bible to become the starting point for an unending, in some views, even infinite oral Law. This ongoing Tanakh is the real Jewish Bible. This is the cultural phenomenon that made and remade Judaism over the ages. Sadly, this is a Bible that Jews started to fear when Christianity came into being with its interpretation of its Old Testament. This is the Bible that the traditional Jewish community moved further away from with the rise of modern biblical studies and the questions of faith it raised in an era in which Reform and Conservative Judaism had come to be. This is also the Bible that Israelis are reclaiming, whether they call it Miqra’ or Tanakh. Perhaps the great challenge to the Jewish Bible as a concept is that it still needs to be fully reclaimed. One final point: they told me to be controversial; I hope I was!

[please note that i don’t seem to be able to enter text in lower case letters, so please excuse the all caps.]

Thank you, prof. Schiffman, for this introduction. I look forward to reading much more on this subject (please write the book!).

I would like to ask you about this statement: “No Jew in the synagogue has ever heard of the ‘Hebrew Bible.'” in my experience there are jews — both inside and outside (usually liberal movements’) synagogues — who have indeed adopted this phrase, and use it when they wish to differentiate the tanakh from the christian testament. some even use the even worse term “old testament” for their people’s own texts. this is another way in which jewish self-understanding continues to be eroded through the influence of christian-dominated culture. do you not find this to be the case?

The most evident solution I ever used is “Torah”……..aNY GOY KNOWS NOW WHAT IS tORAH

Why to look for anything else than our original hebrew Names?????

A very good precis. Just one minor quibble and one minor correction. The quibble concerns the sentence, “Because they were not seen as authoritative, over twenty books mentioned in the Bible did not survive.” We don’t know why those books did not survive, but it seems more probable that, at least in some cases (such as, perhaps, sefer hayashar and sefer milhamot HaShem), the books did not survive because they were lost in the cataclysms at the end of the first Temple period. The correction is in the last paragraph where certainly it was the Torah that was perceived as having been given to the Jews by God through Moses and not the entire Jewish Bible.

LKE,

I will grant you that “no Jew” was too strong. However, you yourself speak of use of this term to differentiate our Bible from that of the Christians, thus confirming my point.

(also seeing only ‘caps,’ but perhaps this gets corrected somewhere?)

I take the discussion of “what is the bible?” in a different — albeit non-academic — way. I see the books of tanach as an ongoing record of interrelationship with g-d. i don’t believe that this relationship ever ended. or ends. i therefore see everyone’s own life as a “book of bible’ — i.e. “The Book Of …(fill in your own name).” but again, this is more of a “homiletic” than an “academic” approach. both have their place and purpose.

There is a closed “canonical” set of authoritative texts (divinely-inspired-through-prophets) that constitute the “Hebrew Bible.” The Jewish bible is not an ongoing and increasing document but is certainly finished as surely as there are no more indisputable prophets, and as surely as the destroyed Temple and cessation of the Levitical priesthood are an evidence of the broken national covenant.

An actual council to determine a canon (which is merely an intelligent and honest recognition by believers of the antecedent revelation) is not necessary, because the appearance of the divinely inspired texts were not ever dependent upon sinful human beings estranged from Yahweh but was effected by Yahweh’s commissioning of his prophets (Moses and others), just as surely as true Judaism was not initiated by Abraham or Moses but by Yahweh’s merciful initiative.

When Professor Schiffman mentions that the bible is open and ongoing for “real Judaism,” he really means that majority of Jews in whom Yahweh has not circumcised the heart (Deut 30:6), or has not removed the heart of stone (Ezek 36: 26), or has not enabled to believe the message of the prophets (Isa 53:1) that a Servant has died as a substitutionary sacrifice for sin (the sent Messiah Jesus). These are that portion that has “remade” Judaism since the resurrection of Jesus and the destruction of the Temple. This is rabbinic Judaism.

I did write a book explaining much of this: Torah of Sin and Grace.

excellent article!!!! I think this points to a much larger issue: the conflation of what is Jewish monotheism with christian monotheism (sic), that somehow the say, mean and are the same thing. i have often pointed out to christian friends and colleagues that there are at least 5 major monotheistic differences between us:

> the torah is not the old testament: translation, punctuation and interpretation is different.

> the jewish “10” commandments are different than the christian “10” commandments (seee first bullet point) – in fact at least 2 of those are not even understood in christianity (“…i am the l-rd…who took you out of the house of bondage out of egypt”; honor the seventh day)

> judaism posits a unitarian g-d, not a trinity.

> full blown judaism (all 613 commandments) can only be fully observed in the land of israel

> judaism is particularistic to the jews with a universal outlook for mankind; christianity posits a univocal universalism that does not understand particularism or separate covenants.” judaism accepts a multi-covenantal view of people and religions; christianity demands acceptance of a single covenantal theory (all under jesus).

these 5 differences form the broad boundaries of jewish belief, practice and covenant. other dimensions could be cited, but these 5 lead to all of those.

canonization

what happened?

at some point, a group of rabbis had to cut, and more importantly, had to seal.

Does that mean that no other books in existence then were “good”? no. Does it mean that everything that was included was left in for purely religious reasons? probably not — example, the book of esther which was kept in because it was popular.

But at some point, the set was accepted.

and afterwards, nothing could force its way in or be taken out.

The point about the term “Hebrew Bible” is that it was coined after the holocaust by those engaged in Jewish-Christian dialogue–the idea was to stop christians from using the term “old Testament,” so the phrase that came into favor was “hebrew scriptures” (used more often, at least in christian circles, than “hebrew bible”).

the underlying intention was to try to rid the christian side of the jewish-christian dialogue of its supersessionism. that’s where academia got it from, i do believe.