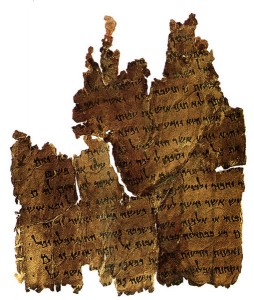

Second Temple Period Rationales for the Torah’s Commandments: Dead Sea Scrolls

In our next section, we consider examples drawn from the Dead Sea Scrolls, in particular the sectarian scrolls regarded as representing the views of the sect that gathered the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran. We will see here that true rationales for commandments are for the most part lacking. We will note a few cases in which rationales are given for various rulings but these are for the most part rationales for minor details, not the commandment as a whole. In fact, we found it very surprising that so few examples could be gathered.

We begin with the Zadokite Fragments (Damascus Document), a text originally found in medieval manuscripts in the Cairo Genizah that later turned up in multiple fragmentary copies at Qumran. In CD 4: 21-5:1 we are given a reason for the sect’s understanding that polygamy is forbidden according to the Torah, and that prohibition included remarriage by a divorced man or woman as long as the original spouse remained alive. The rationale is given as follows:

for the foundation of creation is, “male and female He created them” (Genesis 1:27), and those who entered the ark, “two by two they came into the ark” (Gen. 7:9).

The question here is whether this is a rationale for a commandment or whether it is actually a halakhic midrash, an exegesis meant to support a legal ruling. We will see that in quite a number of examples of the Dead Sea Scrolls it is hard to distinguish rationales from biblical support. One example that clearly is a case of biblical support, rather than a rationale, is the prohibition of marrying one’s niece found in CD 5:8-11.

In 4Q267 frag. 5, col. 3 (etc., p. 78) there appear laws regarding the public reading of the Torah, specifically requiring that it be read by somebody who does not have a raspy voice. The reason for this requirement is given as follows: “Why should he make a mistake in a capital matter?” (line 5). Here we are given a rationale not for a commandment, but rather for a particular ruling of the sectarians in a matter of Jewish law, namely regarding the qualifications of the Torah reader. Clearly, what is motivating this ruling is the fear that hearing an unclear reading might lead to a mistake on the part of a listener regarding a Torah commandment.

Somewhat similar is a ruling of 4Q267 frag. 7 (etc. p. 118) that a man (or perhaps a person) is forbidden to keep secret the blemishes of his (perhaps hers also) daughter from a potential suitor. The reason is given as follows: “Why should he bring upon himself the law of “Cursed be he who leads the blind astray on the way?’” (Deut. 27:18). Here again, the rationale for a sectarian prescription is that if one does not follow it, he will be violating a commandment of the Torah. In a certain sense, this is the reverse of what we would normally expect. Instead of telling us the rationale for a commandments of the Torah, our text advises us how to avoid violating it. The comparison to mixed kinds (kil’ayim), already encountered in Josephus, appears here in line 13, referring to one who gives his daughter to one who is not appropriate for her. This comparison is also made in the MMT document. Although this is close to a reason for the commandment, it again is the reverse of what we would expect. Instead of telling us the reason and what we may learn from observing the commandments regarding mixed animals, seeds and cloth, namely the requirement that we maintain the natural order as God created it, we are instead being told that an inappropriate match is analogous to such mixtures.

Much closer to what we are seeking is an explanation in CD 16:6 for the circumcision of Abraham that is said to have taken place be-yom da`ato, which I take to mean when he reached sufficient consciousness and understanding of his relationship to God. We are indirectly told that on that day the angel of Mastema departed from behind him (14:5). What we seem to learn here is that the ritual of circumcision in some way banishes the forces of evil from the young child and leads to a full understanding by the child of his relationship with God. This certainly seems to be an actual rationale given for the commandment of circumcision, something very rare in the scrolls. It goes beyond the examples of etiology that we mentioned before, since it does not assert Abraham’s circumcision as the reason for that of later Jews. Rather, it gives a reason for circumcision that applies to Abraham as well as to future generations.

CD 9:15 gives a reason why lost property, the owner of which cannot be located, should be placed in the hands of the priests. The reason is, “for the finder will not know its law.” The idea here is that the finder may not know the required laws regarding the maintenance and protection of lost property that has not been claimed, a task that the priests will know how to fulfill. Since giving such property to the priests is regarded by the sect as a commandment of the Torah, this indeed is an example of the giving of a rationale for a commandment.

These examples suffice to give a sense of the kinds of explanations or rationales that are found in the Zadokite Fragments. We now look at a different type of text, the Temple Scroll. This document is essentially a rewrite of much of the Torah. On the other hand, the text seeks to appear like the Torah, and for this reason does not generally add too much material of its own. Therefore, we actually have found only one example, in a section of the text called the Law of the King, that is the only part of the scroll that represents sustained composition by the author, as opposed to rewriting of the biblical text to include his own interpretations and legal rulings. These rulings, by the way, and the interpretations behind them, seem to accord with the Sadduceean/Zadokite approach to Jewish law and exegesis..

11QTa 57:7-8 provides a reason for the requirement that the King have a guard of 12,000 men and that they not leave them alone, “(lest he) be taken captive in the hand of the non-Jews.” However, this is not really a rationale for a commandment, rather for a part of the revised political constitution that the author/redactor of the scroll put forward in response to his dissatisfaction with the political order of the day during the Hasmonean period. There are a few points where the Torah provides motive clauses for commandments and some of these do appear in the scroll. However, the author, who codified numerous Torah prescriptions does not add reasons such as what we found in the writings of Josephus.

Finally, a few examples are found in some smaller legal texts in the scrolls collection. In 4Q 251 (p. 47) we have an explanation for the ceremony that takes place when a dead body is found between cities. Discussing the heifer, the neck of which is broken (Deut. 21:1-10), this text twice mentions that the heifer is “in exchange for the life” and then “it is a substitute” (lines 4-5). This clearly qualifies as a rationale for the Torah’s commandment. In 4Q265 (p. 70) we are given the same rationale as in Jubilees for the periods of purity and impurity for a parturient woman, one who has just given birth. We should finally mention that certain prayer texts that are to be recited prior to ritual immersion make clear that the sectarians saw ritual impurity as based on a moral defect and the need for repentance. [Much has been written on this idea in the Dead Sea Scrolls and we see it as being beyond the scope of this paper.]

Iirc, there’s not a lot of rationalization provided for most of the Mosaic Law. Maybe the communities behind of Dead Sea Scrolls didn’t see that as necessary.