Sectarian versus Rabbinic Theology

Both second Temple texts and rabbinic literature were heir to the complex and often contradictory theological views of the various biblical books. However, it goes without saying that such basic theological ideas of Judaism as God as the creator, revelation of the Torah, or hope in a coming redemption are shared by both corpora. The more important question is whether ideas that are unique to second Temple period texts that represents substantive development from or differences with common biblical notions that are found in the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha and Dead Sea Scrolls are continued in rabbinic Judaism or not. Does tannaitic Judaism in its theology inherit the second Temple literature or does it trace its continuity with the last days of the Hebrew Bible through some other pathway?

Both second Temple texts and rabbinic literature were heir to the complex and often contradictory theological views of the various biblical books. However, it goes without saying that such basic theological ideas of Judaism as God as the creator, revelation of the Torah, or hope in a coming redemption are shared by both corpora. The more important question is whether ideas that are unique to second Temple period texts that represents substantive development from or differences with common biblical notions that are found in the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha and Dead Sea Scrolls are continued in rabbinic Judaism or not. Does tannaitic Judaism in its theology inherit the second Temple literature or does it trace its continuity with the last days of the Hebrew Bible through some other pathway?

An interesting example of this issue is that of the extreme predestination and dualism taught in the sectarian Dead Sea Scrolls. This set of beliefs assumes that God has preplanned the entire course of the cosmos and certainly of humans who are divided into two lots, as are the heavenly beings, who struggle eternally against one another. A person’s actions, for good or evil, seem in this system to be beyond his own power, and yet he is punished for transgressing God’s law, even including prescriptions that are not known beyond the sect. There is no basis for such ideas in the Hebrew Scriptures, and it is widely assumed that these concepts are somehow influenced by Persian dualism. When we arrive at the rabbinic corpus we find that predestination is not accepted, although human free will can be countermanded by God. There is no cosmic dualism, but rather we find an inner spiritual dualism of the good and evil inclination (יצר) in each person. Later, this concept would merge with Hellenistic notions and the two inclinations would be closely identified with the spiritual and physical aspects of humanity. But free will is the basis of God’s judgment of people and all are fully informed of their obligations.

Another example of a notion found in the scrolls, also in second Temple texts, is the notion that prophetic or revelatory phenomena did not end with the story line of Scripture circa 400 B.C.E. but rather continued beyond, into Greco-Roman times. This point of view seems to underlie a lot of material from the period. Yet it is virtually absent from rabbinic literature. The only remnant, the בת קול , some kind of echo of a divine voice, is explicitly declared to be null and void. Clearly the system of Oral Torah and its inward development obviated notions of direct divine inspiration, even if weak. Perhaps most importantly, the rise of Christianity seems to have emphasized for the rabbis their notion that the end of the biblical period meant the end of prophecy and the end of writing of scriptural books.

A few words, however, need to be said about eschatology and messianism. Both of these themes are considerably important in rabbinic literature, with extensive materials devoted to them. This is not to speak of the apocalyptic type messianic materials that appear in post-Talmudic writings and that extensively resemble such texts as the Qumran War Scroll.

Here we must distinguish two separate issues, the question of the nature of the messianic figure or figures, on the one hand, and that of the nature of the messianic expectations, on the other. Put simply, we need to ask first how many and what kinds of messiahs are expected and, second, what kind of events are supposed to lead up to the messianic era, and, third, what its nature will be.

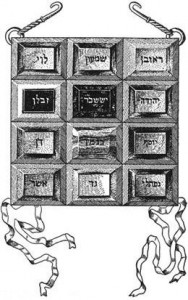

Second Temple texts contain three different views of the messianic figure. Some texts present what I would term non-messianic messianism, in which the eschatological future is assumed to come into being but no leader is specifically mentioned. We cannot be certain that in these instances no such leader is expected; it is simply that no messianic figure occurs in the texts. A second variety, perhaps the most common, is that in which it is assumed that there will be one messiah of Davidic extraction. The third approach, known to us from certain of the Qumran sectarian texts as well as from the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, is the notion of two messiahs, one of Aaron and one of Israel. I emphasize the words “of Israel” because many books simply assume that the Israel messiah is Davidic, a notion with which I have disagreed based, I hope, on a thorough study of the evidence. In any case, Talmudic Judaism assumes that there must be a messianic figure, even though some rabbis argued that the messiah had already come. The dominant point of view is that of one messiah, a scion of David, expected to bring about the messianic era. No serious parallel at all can be quoted for the notion of a priestly messiah from rabbinic literature. Talmudic tradition does, however, speak of a second messiah, a messiah son of Joseph. No amount of searching will reveal the prehistory of this Josephite messiah (referred to in some later apocalyptic texts as a son of Ephraim) in any second Temple text. The upshot of this is that the dominant notion in second Temple times, carried over into rabbinic tradition, was the expectation of one Davidic messiah who would bring about the redemption and rule over Israel as the messianic king. While this approach has extensive rabbinic parallels, other competing approaches seem to have become extinct and not to have crossed the literary abyss that we spoke of before, between second Temple texts and the rabbinic tradition.

On the other hand, a significant difference of opinion among second Temple texts regarding the onset of the messianic era itself is carried over into rabbinic texts. Two trends have always been observable in Jewish messianism: the first trend, the restorative or naturalistic trend, assumed that the messianic era would usher in a return to the great glories of the ancient Jewish past. A second trend, the catastrophic or utopian, assumed that the messianic era would usher in an era of total perfection, one that never had existed before, in which all evil and suffering would be eradicated. While the naturalistic messianic approach assumed that the messianic era could be created by the gradual improvement of the world, the catastrophic or utopian assumed that a great war, often termed the Day of the Lord, would lead to the total destruction of the wicked and the onset of the eschaton. Both of these views existed in second Temple texts, but Dead Sea Scrolls materials particularly emphasized the catastrophic and apocalyptic–the assumption that the great war of the sons of light against the sons of darkness, in which all but the sectarians would be destroyed, would bring on the messianic era.

This very dispute is reflected in rabbinic texts, where we find Talmudic sources supporting the onset of the messianic era under either peaceful or violent means. Further, some texts speak of a naturally improving world, where others speak of perfection attained as miracles bring on the messianic era. Both trends visible in second Temple literature are visible in the rabbinic corpus. In this case, it is simple to account for this situation. This dispute regarding the messianic era was part of the common Judaism of the Greco-Roman period and accordingly passed, with no literary framework necessary, into the thought of the rabbis. We may observe here that rabbinic thought in the aftermath of the great revolt and the bar Kokhba revolt tended to the more quietistic approaches to messianism. With time, however, the apocalyptic militant notions resurfaced in amoraic times.

There was also a debate during second Temple times about the significance of the messianic era and its nature. Clearly, to those who advocated the Davidic messiah, he was to accomplish the restoration of Jewish military power and national independence, and to rebuild the Temple, which was the goal of the messianic era. On the other hand, it was expected by others, who emphasized the two-messiah concept in which the messiah of Aaron was most prominent, that the true purpose and perfection of the eschaton would be the restoration of the Temple to the standards of holiness and sanctity which it deserved. (We must remember that the second Temple texts were composed while the Temple still stood.) In the aftermath of two Jewish apocalyptic revolts and the destruction of the land twice at the hands of the Romans, the rabbis sought a restoration of the Davidic glories of old, of a political entity secure and independent. Apparently, in their view this would insure the proper rebuilding of the Temple. Yet they did not see the Temple as the central act in the messianic drama, rather as a part of the process. For this reason, the Aaronide messiah has no parallel in rabbinic literature. This is the case despite the fact that Eleazar the Priest appeared with Bar Kokhba on coins, conjuring up the messianic pair of the nasi and kohen.

Leave a Reply